They got married in the midst of Illinois’ worst winter storm. With the odds against them, what has made their nearly 50-year marriage last?

Part 2

Read Part 1: A mother, a ring, and America’s hunger

Mom wore a red plaid flannel shirt and faded flared jeans. Her brown-blond hair fell below her shoulders, pinned back from her face with a metallic drugstore barrette. She wore thick brown aviator glasses, the strong prescription minimizing her blue eyes and breaking the line of her high, wide cheekbones. She wore minimal makeup: some mascara, and Carmex lip balm on her downturned smile. She did not have a ring. She borrowed one from my Aunt Pat, her soon-to-be sister-in-law and a witness to the union.*

The guests all dressed in similar fashion.

Her dad wore a scowl.

Mom was 18. Dad, 22. They had met just four months earlier at Howard Industries, a motor manufacturer for refrigerators in Milford, Illinois.

“Everyone worked there until they could find something better,” Mom said.

But Mom had seen Dad once before.

“I was walking down Main Street. I saw a maroon-colored T-bird with a blond-haired guy driving that I had never seen before. It was the first time I laid eyes on him.”

The next time she saw him was at work. They talked during a couple of jobs they did together. Then one day he asked her out.

“We dated a couple of times, then he invited me to go to church. The first time I ever went, I got saved. I got baptized in November in a pond in the cold.”

That November was the start of the worst winter ever recorded for the state of Illinois. It started with a late November snowfall and continued through March: high winds, the coldest December–March (average 22 degrees), record-breaking prolonged heavy snow cover, and 18 major storms (eight of them blizzards), including the “super storm” of January 1978.

Weather forecasts of a potential storm started coming in on Tuesday, January 24. Two storms, one from the north and one from the south, were racing toward each other. By the next day, meteorologists warned of a severe blizzard. By Thursday, almost everything had shut down. The storm lasted through the 29th.

That Saturday, Mom and Dad sat talking in Uncle Larry and Aunt Gail’s spare bedroom.

“We were always at Aunt Gail’s or Aunt Pat’s,” Mom said.

They visited Dad’s sisters and brothers-in-law most weeks. Despite the snow outside (Midwesterners navigate several inches of snow most winters), my parents thought it reasonable that this week be no different.

However, once they were there, it started to look like they might have to spend the night. Mom still lived with her dad in town, but Dad lived 35 miles away in Milford. Temperatures were dropping, it was starting to snow again, and the wind was creating giant drifts. Hoopeston’s two plows broke down and a neighboring municipality had pitched in to help.

“Route 1 in Hoopeston, every time it snowed there, the wind started blowing, and that would cause the snow drifts,” Mom said. (When plows finally made it out to Route 1 between Hoopeston and Danville, to the south, snow piled higher than the cars in some spots.)

Mom and Dad had already been talking about getting married, but with Dad a preacher and Mom now a member of Beautiful Home Missionary Baptist Church, the prospect of sleeping in the same room fast-tracked their talks.

“We already had everything ready to get married in February,” Mom said, but they hadn’t been able to nail down a date. “We had the paperwork. Then there’s the storm, and we were there, and at the time, Dad thought, let’s go ahead and do it now. So we could spend the night there. Kind of silly, but, that’s how we were thinking.”

They had the paperwork and the officiant (Uncle Larry), but they still didn’t have a ring, and they needed witnesses. Aunt Pat and Uncle Rick lived in town.

“If Pat and Rick have to be there, then my dad had to be there,” Mom said.

So she made the call.

“I tell my dad, hey, we’re getting married. He asked me a couple of questions, like, ‘What are you talking about?’ and ‘You know there’s a blizzard outside?’”

And finally:

“Are you sure?”

Then he grumbled about the weather and made his way.

Aunt Pat and Uncle Rick made it to the house, as did my parents’ friends Paul and Linda, who also lived in town.

Then Mom’s dad arrived and had a few things to say to Dad.

“It was something to the effect: you better treat her right,” Dad recalled, “and he gave me a look. It wasn’t a loving look, I can tell you that. I told him, I’ll take care of her.”

The wedding party was assembled.

“So we get married,” Mom said, “then we decide, your Dad already had a place in Milford. He decides we’re going out there.”

They made it home.

But Mom didn’t just marry Dad that day. She also married the Church.

The role of preacher’s wife is a precarious one and largely undefined.

Dad became an ordained minister a few years after they got married, then became pastor of their church a couple of years after that. By then, they had three kids and moved to Ambia, Indiana, just over the state line from Hoopeston.

Growing up, it seemed like we were always traveling. Preaching in the rural Midwest meant several miles of driving between small towns and expansive fields. When Dad was asked to preach, it usually meant a morning of driving, two hours of church, a midday meal somewhere, an afternoon of visiting, another hour of church, and the trip back home. For revivals, it would mean a regular weekday of school and work, followed by an evening of travel, church, and then home, multiplied by however many days the revival went on, sometimes a week.

It wasn’t easy, Mom said, but things always seemed to work out.

“Our lives got a lot better when we finally gave it up to God.”

On at least one occasion, Dad avoided a layoff because he answered a call to lead a church. Dad never got paid to be a pastor. Most churches can’t support a full-time pastor. The average church attendance in America is around 60. Rarely did any of ours top 50. At a church with 50 to 100 attendees, pastors might make $40,000. And sometimes they’re putting in 100-plus hours a week.

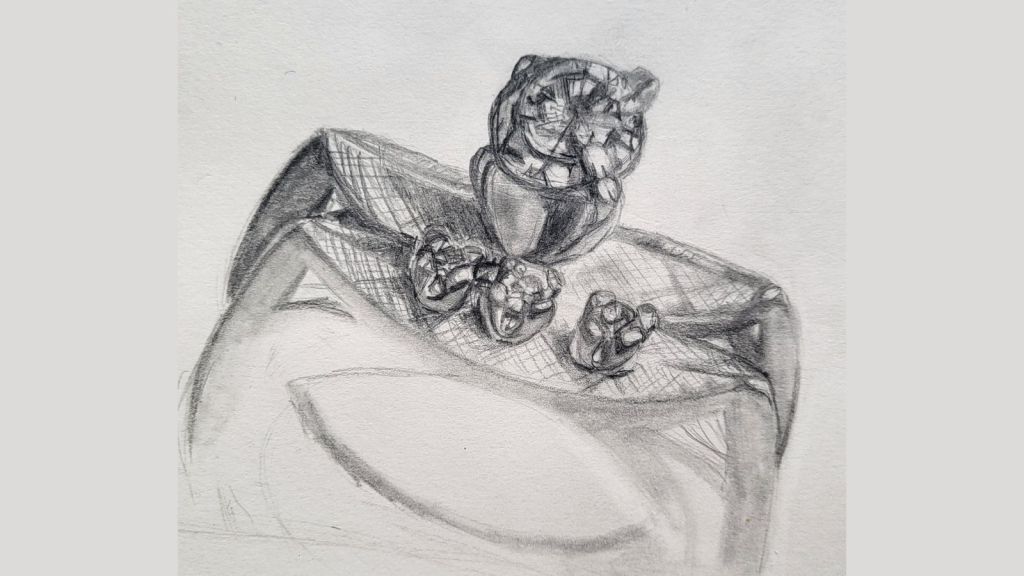

It was also around this time that Dad started working full time at FMC and wasn’t getting laid off every summer. With some money saved up, he walked into the Unger’s Jewelry store in Hoopeston, where he had sold the ring he found a few years earlier, to buy Mom a ring.

He found one unlike any he’d seen before or after: The bands interlocked and the tops were a flattened, concave knife’s edge that curved up and reverse-tapered to smooth points on the sides. A round solitaire diamond sat on one band, and three stones on the other.

“Three diamonds for the three of you kids,” Dad said, “and one diamond for the rest of our lives.”

When I asked Mom what her experience was being a preacher’s wife, she floundered—starting sentences she didn’t finish or giving examples she couldn’t quite remember, trying to piece together all the aspects of not only her own role in that position, but the larger expectations placed on it.

Finally, in an attempt to help clarify, I likened it to being the First Lady.

“Yes! Exactly!” She threw her arms up.

The job description is vague, there’s no real mention of it in our church manual, the Bible devotes only 11 verses to it in Timothy 3, and the position, for the most part, is unpaid.

In her book The Preacher’s Wife, about the rise of megachurches in the 1970s and 1980s and the quasi-celebrity of the women who arise out of them, Kate Bowler uses “first lady” interchangeably with “preacher’s wife.”

On top of the demands of women to be wives, homemakers, caretakers, and anything from household breadwinner to coupon-cutter, a preacher’s wife, as Bowler’s book describes, is also expected to be “hard-working,” polished,” and “wholesome.”

The role of preacher’s wife has varied from the quiet, doting wife sitting in the church pew to the warm and welcoming extrovert who hosts luncheons and Bible studies. From Billy Graham’s wife, who spent most of her time at home with their kids while he traveled, to all the cringe and controversy of Tammy Faye Bakker.

“When you say ‘preacher’s wife,’ there is this idea of what that is and what it entails,’ Mom said. “I’m not that.”

When you say “preacher’s wife,” there is this idea of what that is and what it entails. I’m not that.

Mom has been a Sunday school teacher, secretary and treasurer for the church, and has even made unleavened bread for communion.

Most of the time, Mom’s job was just shushing us kids in the back pews.

Sometimes she felt as if she needed to be an aid-giver, marriage counselor, and problem-solver for their congregations. But she has been careful not to take on too much or let people believe her job was anything more than helping support Dad in his work.

“We had a marriage like anyone else,” she said. “We had to work at our own marriage, solve our own problems, raise our own family.”

But at one point, it was the church that almost made their marriage break.

For Mom, one of the hardest parts of being a pastor’s wife was watching the weight of what Dad carried, and not being able to do anything about it.

We had moved to Tennessee from Indiana to be closer to Dad’s family and find a church. Dad became lead pastor and had the help of another pastor there to fill in or switch up duties when they needed to. The church was growing and attracting young families.

Dad was welding and bringing in new clients for M.E. Industries, a refueling equipment company for aviation companies and the U.S. military.

We kids had settled into school and made friends.

But as things were at their best, it started to fall apart.

Dad’s work was busy, and he was working overtime, into the nights and on Saturdays. He was also starting to study for his inspector’s license.

My older brother was about to get married, I was going to start college, and my younger brother was jetting off to the first city that would let him in.

Then one of the core families at the church left.

In our church, that translated to almost 20 percent of the congregation. It was hard on Dad, between the overtime, us kids leaving the house, and then this.

“I thought he was getting sick,” Mom said. “If you look back at the pictures, he didn’t look good.”

I went back to the pictures. Dad looked like a thin, tired, sad Ed Harris. In one, he’s standing outside the church, and his clothes look loose, his belt fastened around folds of his slacks.

Mom was used to voicing her opinions and thoughts, and Dad would sometimes come to her when he needed her input. But this time, any conversation about it turned into an argument.

Mom withdrew.

It’s still difficult to have this conversation, even today.

So I go back to the family photos again. There are a few years of somber faces. Then photos of Mom and Dad together, on hikes, posing like newlyweds, or separate, staring off into the cropped landscapes.

Eventually, Dad got his inspector’s license and was offered a job with the State in Oregon.

This January, they’ll celebrate their 48th anniversary.

From the outside, my parents did almost everything wrong.

They got married too young. (Age was one of the top indicators of divorce during the steep incline of divorce rates following the 1950s, when the average age of women was 20 and men, 22.)**

They didn’t have enough money. (About 50 percent of marriages in low-income neighborhoods end in divorce, separation, or abandonment within 15 years.)

Or education. (Within 20 years, 60 percent of women with a high school diploma divorced, compared to 22 percent of college-educated women.)

And they didn’t have a ring. (One infamous study showed a connection between higher-priced engagement rings and divorce rates, although that same study actually showed no ring was almost as successful in reducing the chance of divorce.)

So what happened? What made this one stick?

On one level, the answer is easy:

“You can’t just split up at the first signs of trouble,” Mom said.

But there’s something else that stood out in my conversations with my parents.

When I asked Dad why he wanted to marry Mom, he told me:

“We needed each other. The love was there, but mostly it came later.”

We needed each other. The love was there, but mostly it came later.

In the book The All-or-Nothing Marriage,*** Eli J. Finkel touches on that very subject. In trying to explain the evolution of marriage, its near downfall in the late last century, and now the modern-day struggles, Finkel aligns a successful marriage with Abraham Maslov’s hierarchy of needs. And at the foundation of that hierarchy is safety and physiological needs: food, shelter, security.

Practically speaking, it’s easier to survive, even and especially in the modern world, when there are two of you combining efforts and pooling resources.

For the past 100 years or so, we’ve been somewhere around the middle of this hierarchy. This is where the relatively new idea of love and marriage lies. And it’s why, according to Finkel, in combination with all the cultural turmoil of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, divorces rose precipitously and nearly crumbled the institute of marriage in America.

Mom and Dad said the hardest part about their marriage was trying to communicate.

Dad came from a family where his dad made the decisions and no one argued. Dad believed you should never fight in front of the kids.

Mom came from a world where her parents fought constantly and divorced when she was 15. She believed in putting things out there. Today, she thinks the best path might be somewhere in the middle, where you try not to fight, but if you do, it’s best that children see the resolution.

That’s who Mom tends to be: The girl who barely finished high school, to the woman who continues to learn long into her 60s. The kind of woman who comes from a divorced home and makes a lasting marriage. Leaves Chicago and takes on a farm. Didn’t go to church and became a pastor’s wife. Says she’s not creative but can pick up nearly any craft of project.

And that’s the woman I’ll be visiting in the final installment of this series.

Author’s Notes

*Despite searching, I’ve not been able to find a photo from my parents’ wedding, though I could swear I’ve seen it before.

**Unless otherwise noted, these figures come from the book The All-or-Nothing Marriage and then were cross-checked with articles and online sources.

***Affiliate link. Any purchase through this link supports me and my work.